I inherited my blue eyes from my father, along with his wanderlust. One of these traits society deems beautiful, while the other is rebuked, should the person be a parent. I’m a parent myself now to an intelligent, curious, kind 11-year-old boy whose passions are Pokemon and dinosaurs. My wanderlust is tamed as I prioritize my son’s needs, but my father did the opposite. In fact, the last time I saw my father in person was over a decade ago in Houston, Texas. He died on Jan. 14 of sudden kidney failure. While several addictions plagued his life, alcohol was the one he indulged most in, and ultimately the one which sealed his fate.

For a long time, I envied my father and loathed the man, feeling abandoned by him over his addictions. I was pulled from my mom’s care at age eight, then resided with my maternal grandparents until the age of 11 when I entered the foster care system. Following that event, my father basically abandoned me, chasing different vices to avoid facing the hard truth, which was his contribution to my home environment disruption. My parents divorced when I was five, and the truth is that his addictions directly impacted their marriage and my relationship with my father. The man was not perfect, but he was not entirely without good intentions. A brief stint he had in a local prison resulted in letters he wrote to me, with long words which I used the dictionary to learn the meanings of.

Dad took pride in his last name and how he could share it with me. In fact, my name alone is a memorial to such a complicated life – whichever religion I was baptized in (Mom was Presbyterian, Dad was Catholic), the other parent would get to name me. My father chose the name, Danielle, meaning “God is my judge,” and I was baptized Presbyterian. I learned later in life that my father’s choice of drugs may not have been much of a choice, as mental issues compounded his usage. Also, family rumors spread about him being illegitimate, likely contributing to such choices. I cherish our conversations, especially in recent years, as we grew closer and mended our familial bonds. He never liked me cussing, as it is “unladylike,” but he also grew to accept it as part of me.

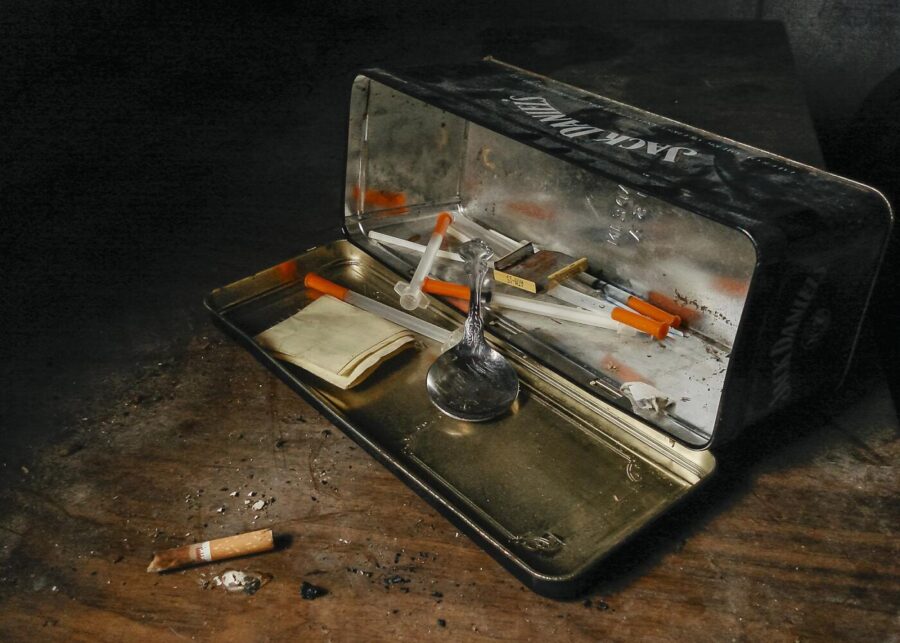

Last year, my father had a health scare which I only found out when his boss, Dave, reached out to me as I was Dad’s next of kin. Dad was fine, embarrassed if anything, because the hospital installed a stoma bag, or a sh*t bag, per Dad’s language. I almost dropped everything with my courses, intending to make the nine-hour drive to see him. Dad stopped me, reminded me of my responsibilities, and told me he was fine; he just needed to rest. As much as I hate that I didn’t go to him, I acknowledge that my father would not have wanted me to shirk the opportunity I’ve had to return to college. Dad was sensible and practical, even when he used drugs. A story we shared that’s worth telling is one where he warned me away from a hard street substance.

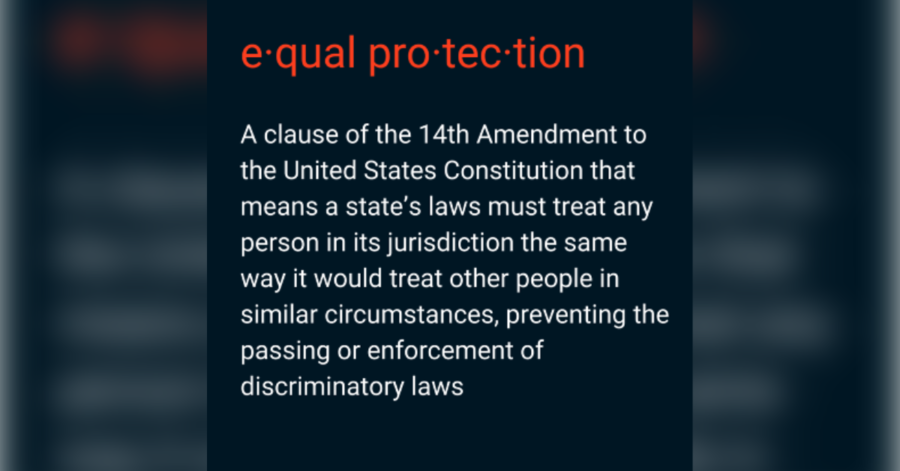

“You wanna know why you don’t use crack,” Dad’s voice fluctuated over the phone. When I asked him why, he replied, “because you’ll take a baseball bat to a parking meter over a couple dollars in front of a cop.” His Peoria County police record list alone consists of 26 offenses, with six being criminal felonies and an additional six being criminal misdemeanors. As a young adult, I didn’t recognize the importance of how being related to my father would impact me until I stood before a judge who recognized our last name. After she inquired about my relation to him, she told me she “…never want to see your face in my courtroom or your name across my docket.” I wisely took her advice and haven’t returned to grace her presence.

Dad’s criminal history stretches as far north as Elgin and as far south as Florida- and though he never went east, I know he graced California and Texas for a few years each. With some new ventures, such as his travels in California, our relationship became strained. I grew tired of 2 a.m. phone calls from a man spinning out of his brain, convinced that the FBI was after him. I lost sleep calling hospitals, morgues, police departments, and rehab centers when his cell was out of service or traded for a quick high. I withdrew his access to myself and his grandson, refusing calls, pictures, or any information. He never shamed me for such decisions as his head became clearer these past couple of years. If anything, he reassured me that he respected me for doing so. It doesn’t make his loss any easier, as many years have been lost and cannot be reclaimed due to his death.

Despite mixed feelings about my father, I cannot ignore living in his shadow. Not only do we share our love of seeing new places and people, or our blue eyes, which turn gray when we are deep in thought, we share a love of writing, music, and jokes but, above all, helping other people. My father, no matter his status in life, when he had an apartment or was homeless, would go above and beyond to help his fellow man. He complained a few times about eating less because he made sure a neighbor wouldn’t go without a meal or that someone had stolen something from him from a shelter, but being cruel to others or dismissing their needs was something my father could never do. It’s a commonality we shared, which I only recently embraced. I’m slowly embracing his death more, and though I accept the finality, it doesn’t quite make the loss itself lesser. I found a marble the other day in the strangest place in my apartment, and while my father never graced my doorstep, the man loved shooting marbles from his slingshot. He took great pride in such an “odd” skillset.

The death of a parent is no small thing, and it’s not an instance many of my family or friends can share with me. Not that I would wish that they did. Reflecting upon my dad’s life, though, his flaws, actions, and inactions, I find myself recognizing that addiction itself was not the person I came to love and call my father but an aspect of his life that he desperately fought to control when he was mentally competent enough to fight back. Addiction isn’t a game; it’s a gamble in which one’s life is literally rolling out of control as the addict watches on helplessly. My father lived many years of his life homeless, and he died homeless, as was his choice. I take comfort that he had the will and mental state to seek help at a local hospital, so he did not die alone, though I have to acknowledge that his lifestyle, over the course of both of our lives, is what ultimately caused his death. I am proud that I have the competence to avoid such choices, though my own mental health fluctuates. But I mostly take great comfort in how proud of me my father was not to have followed in his shadow in that regard.

In loving memory to David T. Webster. My father, my friend, and now my guardian angel.