Generational trauma is difficult to examine and even more difficult to appreciate on a personal level fully. To understand generational trauma, one must understand the trauma’s source and the context and conception the recipient party has for that pain. How they conceive of themselves and their pain and perceive their relationship with other people’s pain is yet another layer to this difficult and sensitive equation. Even more complicated is the issue of whose trauma is worthy of examination and to what extent said trauma applies to the modern-day descendants of the victimized group. Examining even a handful of these questions can prove illuminating and reveal legacies long ignored. Therefore, it may seem surprising that anyone would examine the relationship of generational trauma in Irish migration to the United States, as much of the relationship Irish culture has had with modern America has been largely commercial and surface-level. However, examining how Irish identity became a part of America’s view of itself can reveal just how traumatizing and dangerous xenophobia is.

Understanding the historic origins of Irish immigration to the United States requires understanding the long-term rule over the Irish Island and territories. Though several centuries of conflict between Ireland and its neighbors contributed to long-standing conflict, contracts, and stolen territories, it was the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 that set the stage for what would later be centuries of rule by the English via the Treaty of Windsor under Henry II, who would later send his son, John, to ensure the Irish’s submission to the English crown.

What followed is as complex as it is abusive. Political institutions, which had previously belonged to the clans of Ireland, would be altered heavily. After over 300 years of the initial Norman invasion, Ireland was nominally subjected to the English crown, with the War of the Roses preventing the English crown from fully establishing itself as the dominating force in Ireland. However, that would change after the war’s end in 1485, with the English crown reestablishing its stability and its ability to enforce laws on other territories it held under its dominion.

With the English’s control largely diminished, King Henry VII appointed Sir Edward Poynings to the position of Lord Deputy of Ireland. From his position, Poynings established the so-called Poynings law of 1494, which required all acts passed by the Irish parliament to be approved by the English parliament and crown. Such imposition meant that even though the Irish people technically possessed the right to a government, they were effectively subordinate to a foreign authority over which they had no control.

The situation would only get worse with the establishment of the Ulster Plantation system, established in the 16th century by James I, which created a colonization system that would see Irish ownership of their homeland destroyed by the arrival of English and Scottish colonists after much of the Irish populace was expelled to other countries due to their Catholicism. This process of property-based and political disenfranchisement would not end for over a century and would lead to the further exploitation of the Irish natives.

The situation would not improve in the 17th century with the establishment of the so-called Penal Laws. Among some of the statutes in question was the Education Act of 1695, the Banishment Act of 1697, the Registration Act of 1704 and 1709, and the Disenfranchisement Act of 1728. These policies resulted in the denial of higher education for Irish Catholics, the prohibition of Irish Catholics from owning land above a certain property value, and the prohibition of Catholic traditions and clergy within Ireland and England. It is worth noting that all of these served as an attack on Irish identity, as Ireland had a strong tradition of Catholic education and syncretism with their Celtic traditions. Though the acts would be repealed and eased by the end of the 18th century, Irish Catholics possess only about 5% of the land in Ireland, their home country.

Though some rights were restored to the Irish parliament in 1782, thanks to the work of Henry Grattan (a Protestant), his work to establish Irish rights would go much further than that, undermining the English Privy Council’s control of the Irish Parliament and opposing, albeit hopelessly, the Union of Ireland with the English crown. However, political ramifications would soon be subsumed by a disaster that would not only send the Irish population into disarray but also create an entirely new community in the United States.

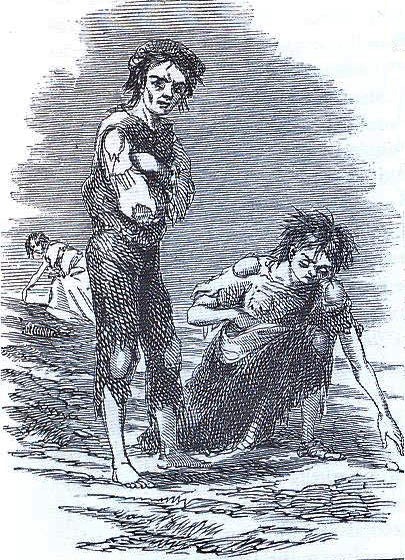

After years of enforced trade and subjugation, albeit resisting subjugation, the Irish natives had become dependent upon the potato for food. Many poor tenants depended on the support of the landlords who, mind you, had much of their land thanks to English colonization. That dependence on the landlords and a single source of sustenance as the main culinary support would lead to disaster between 1845 and 1849. A blight struck Europe, destroying the production of potatoes. Though most countries had suffered the blight, Ireland suffered the most, as the main food source was completely lost, resulting in the tragedy known as “The Potato Famine.”

The famine resulted from a series of inadequate and downright neglectful policies by the English government, with much of the burden of the famine being on the Irish tenants and the poor themselves. Poor laws established by the English government required the able-bodied to work in workhouses rather than receive direct monetary or sustenance-based support, leaving many Irish people subject to the exploitation of their labor. However, some food kitchens were established to support the starving Irish.

Combined with the failed efforts of the English government with a certain level of bigotry by English intellectuals against the supposed Irish character, the negligence had its consequences. Whereas the population of Ireland had been 8.4 million in 1844, it declined to roughly 6.6 million by 1851. While estimates vary, it is suspected that as many as 2 million Irish people died during the famine. But more than that, the Irish would compromise an estimated 49 percent of the number of immigrants who immigrated to the United States between 1841-1850.

Such emigration was not without extreme emotional suffering. As a result of much of the Irish community’s flight to America, many families were split apart to the point where ceremonies were established for those leaving the country, as family members said their goodbyes to their loved ones, who they would likely never see again. The sorrow of these ceremonies was so emotional that they became known as ‘American Wakes,’ as they served as de facto funerals for the lost loved ones who would almost certainly never return to Ireland again, assuming they even survived getting to the United States.

The consequence of that immigration would be an extreme example of American xenophobia and violence. As mentioned earlier, in 1841-1850, there were a series of violent clashes between Irish immigrants and the anti-immigrant Nativists, who saw immigration from Germany, Ireland, and Scotland as a threat to Anglo-Saxon control of American society. In 1844, Nativists attacked Irish-American communities in Philadelphia, burning and destroying Irish Catholic communities after Bishop Francis Patrick Kenrick objected to the required use of the King James Bible, largely used by Protestants, prompting riots among Nativist forces as well as the death of one Nativist. The Nativist Riot of 1844, as it would soon be called, would eventually be subdued thanks to the local militia, but it served as a reminder of the violence that existed with the Irish presence being rejected by xenophobes.

As mentioned earlier, it is critical to understand how one group’s traumatic history interacts with other groups of people. And that is no less evident in how Irish Americans interacted with the African American populace in the 1860s.

Years of fighting and political maneuvering allowed the Irish to establish themselves as strong laborers and supporters of the Democratic party, but by the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, issues of slavery, distrust of the Republican party – which the somewhat anti-Catholic Whig party had preceded – and general ethnic tensions in major American cities, meant that the Irish American populace became less inclined to support emancipation and, in some cases, to support the Confederacy in their bid to secede from the Union.

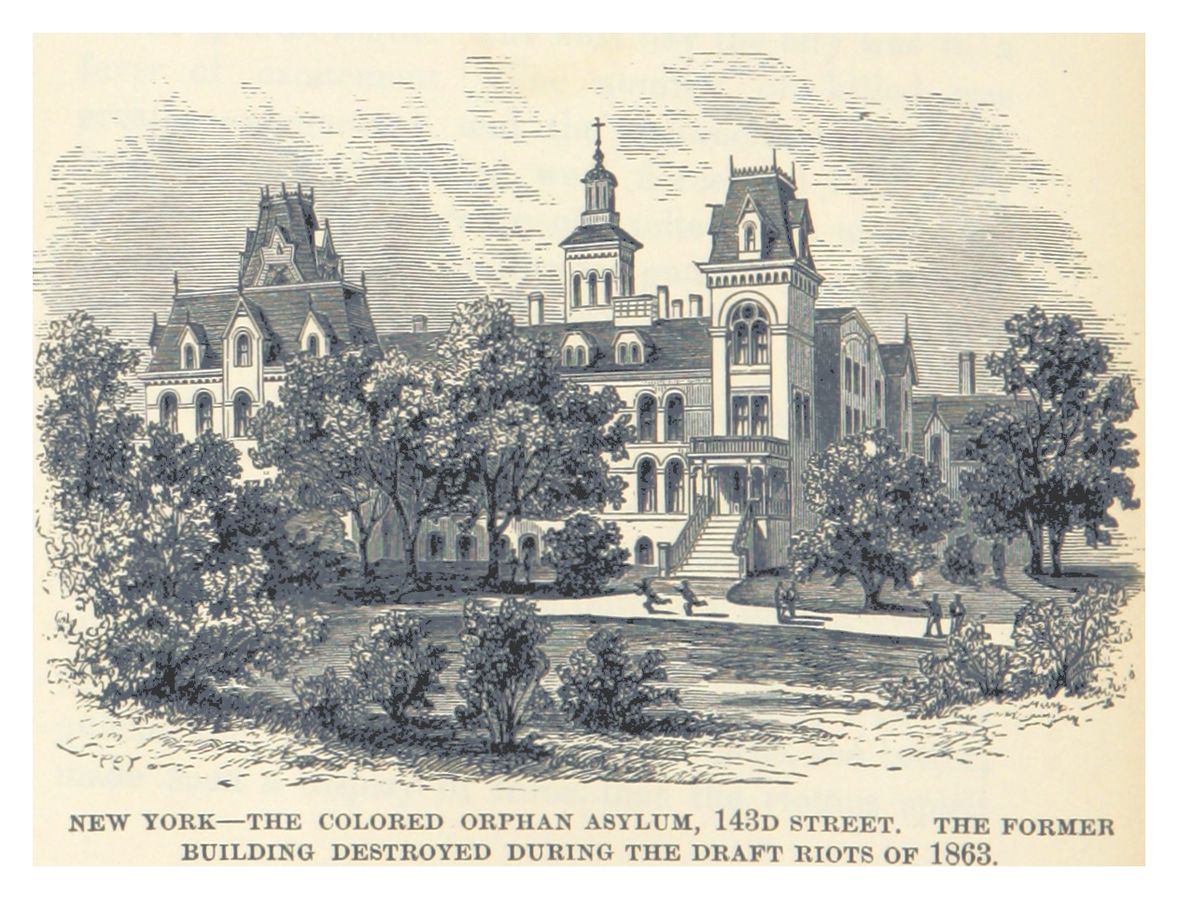

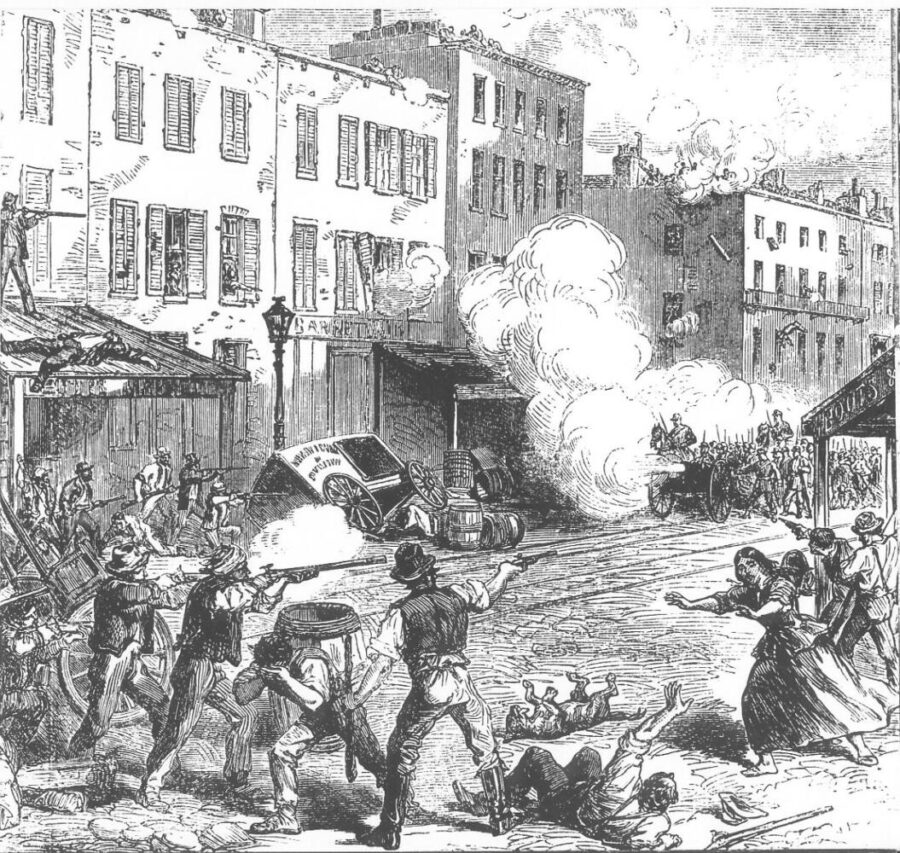

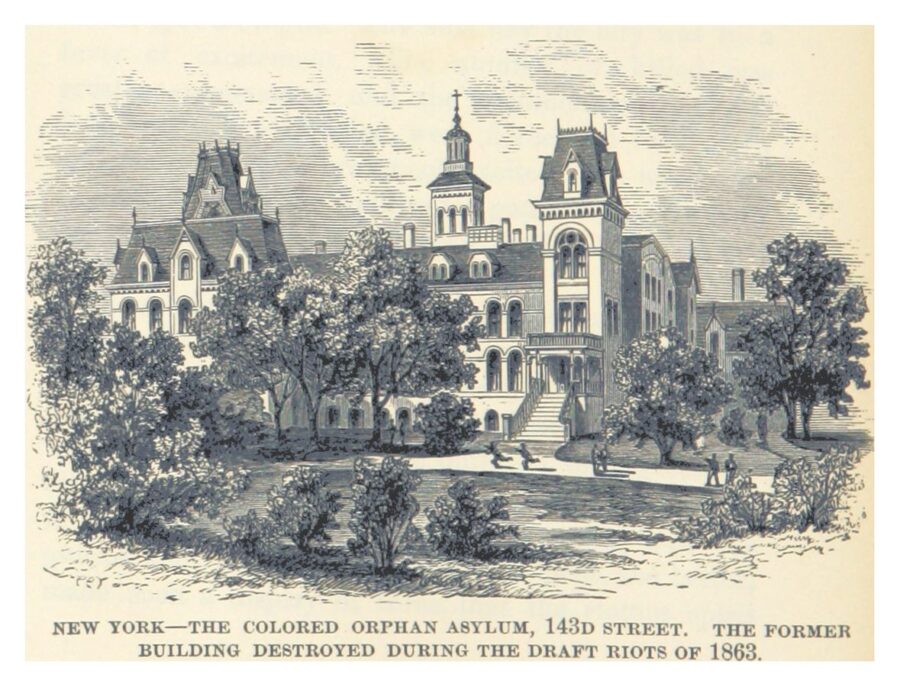

The result was an explosion of racial and class-based violence against the draft instituted by then-President Lincoln. Irish, Scottish and German immigrants in New York rioted against a draft that they saw as serving a rich man’s war. But far from being a solely class-based rejection of the power of the wealthy in New York, the riot was prompted by hatred against African Americans, who, at that point, could not serve yet in the Union Army. The result was horrific and unacceptable violence against innocent Black citizens. Rioters burned an orphanage for Black children and lynched multiple African Americans in the street. By the time the militias arrived under Lincoln’s orders, over a hundred people would die in this horrific riot.

While this is not entirely representative of the Irish experience in America, it does serve as a sobering moment. While the Irish have been historically oppressed, it is equally true that they can be oppressors and were more than willing to do so against their fellow abused brethren. Blinded by prejudice and self-interest, some significant Irish people were willing to assimilate at any expense. And though there were some, such as the famed Irish Brigade, which fought for the Union, the riots of 1863 and the resulting and continuing hostility that some Irish Americans hold towards African Americans should serve as a reminder that trauma for one group does not absolve that group of considering the pain of other groups. Had Irish Americans seen their African American counterparts as competitors as fellow exploited people, they might have been able to help one another. Instead, many Irish people chose prejudice, and while many Irish people today reject the idea of such prejudice, there is still an element who wish to point to the prejudices instituted by English rule as a mechanism to ignore the suffering of modern-day African Americans.

Suppose there is ever to be an understanding of common help for exploited people. In that case, Irish Americans must simultaneously drop the commercialized understanding of their heritage and acknowledge that Irish American heritage is just as tainted by prejudice as any other heritage group in the United States. I am not suggesting that Irish Americans should feel guilt. The grandfather’s sins do not pass to the grandson, but it is the responsibility of those who witness abuse and the long-term consequence of that abuse to respond and help.