When thinking about Black History Month, Black historical figures who hail from Illinois don’t always come to mind. If such figureheads are recalled, the Obama family often comes to mind due to Barack Obama becoming the first Black President of the United States of America. Perhaps the late comedian Richard Pryor, who hailed from the central Illinois city of Peoria, is remembered. Regardless, there are many other Black Americans whose lives or actions changed both Illinois and National history and whose legacies are far too often overlooked. Their stories, lives, deaths, and societal contributions live on in ways they may have never imagined.

The beautiful, bustling city of Chicago is often known worldwide as the “Windy City.” Despite its now-expansive landscape, the city today came from a modest start, beginning with a man named Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. Though little is known about his early life, he is recognized as the first permanent non-Indigenous individual to settle in what is now Chicago. It’s been theorized that Point du Sable was born in Haiti and, as a young man, began trading in North America, which led to his settling at the mouth of the Chicago River. Point du Sable is recognized as the “Founder of Chicago” due to his being recorded in a trader’s journal dating to 1790 as being married to a Potawatomi woman, Kitihawa, at this location. Point du Sable’s trading establishment has been recognized as the first permanent settlement, which grew over time to become the city of Chicago. No authentic portraits of Point du Sable exist, though a sketch of his former homestead survived and was published in 1857.

Though born into slavery in Mississippi, the Emancipation Proclamation freed infant Ida B. Wells from its cruel institution. Wells found work as a teacher in her young adult years, going on to write articles covering incidents of racial inequality and segregation incidents across the southern United States. Despite threats, intimidation, and destruction of presses and an office, Wells voice was shared nationally in Black-owned newspapers to advocate for justice while showing the truths about lynching events. She even won a court case against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad following her refusal to give up her seat on a train car in 1884. Wells would go on to marry a Chicago attorney, Ferdinand Barnett while continuing her anti-lynching work. Frederick Douglass praised her work, even offering financial support for her investigations. However, after his death, many balked at the idea of a woman taking the reins for the Black civil rights movement. Wells advocated not only for Black civil rights but for the women’s suffrage movement, calling for equal opportunities to be offered. At one point, Wells was placed under surveillance by the U.S. Government as a “dangerous race agitator,” though she defied this by continuing her civil rights work. Wells died in Chicago in 1931, though her legacy has not been forgotten. As recent as 2020, she was posthumously honored with a Pulitzer Prize special citation, awarded for her “outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans.”

Chicago-born teenager Emmett Louis Till drew national attention following his death. Till was 14 when he visited relatives near Money, Mississippi, in 1955. Till would be accused of flirting with a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, the white owner of a grocery store he’d gone into. Later, Bryant’s husband and half-brother, Milam, would go on to abduct, torture, and lynch Till in an act of violence that would go on to be exposed in an international light. Till’s mother, Mami Till Bradley, opted for an open-coffin funeral, leading to images of her child’s mutilated body being published worldwide. Though Till’s murderers were found not guilty by an all-white jury, a decade later, they would go on to publicly admit how they had killed Till. Till’s death is often cited as a major contributor to the American Civil Rights Movement. The act of lynching as a federal hate crime was only signed into law in 2022 by President Biden.

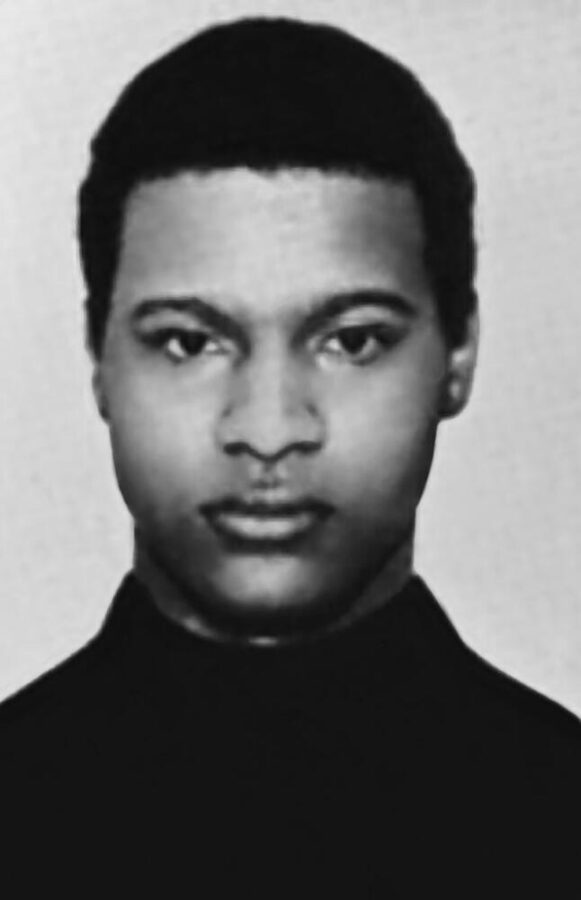

“I believe that I will be able to die as a revolutionary in the international revolutionary proletarian struggle. And I hope that each of you will be able to die in the international proletarian revolutionary struggle, or you’ll be able to live in it.” Posthumously, Fred Hampton’s words live on in an American documentary film, The Murder of Fred Hampton (1971).

Fred Hampton, the Chairman of the Chicago Black Panther Party, was assassinated by members of the Chicago Police Department in an early morning raid of his apartment on Dec 4, 1969. Mark Clark, the Defense Captain of the Peoria Black Panther Party, was killed alongside Hampton that morning. Both men’s contributions to their respective communities are remembered up to the present day. Clark organized the Peoria chapter of the Black Panther Party, then organized a free breakfast program to benefit the community. Hampton worked in Chicago to create the Rainbow Coalition, an anti-class, anti-racist, multicultural movement. The Rainbow Coalition succeeded in uniting differing ethnic groups in supporting one another at strikes, protests, and demonstrations. The Rainbow Coalition sought to recognize that while racism, poverty, and police brutality play a role in systematic oppression, each contributes to a greater issue related to how different social classes are systematically oppressed. Unfortunately, Hampton’s actions did not go unnoticed; FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover condemned the Black Panthers as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” and a raid was conducted. An inquest later would rule the deaths of both Clark and Hampton to be “justifiable homicide” though a lawsuit was filed on behalf of relatives of both men and survivors of the raid on the grounds that civil rights had been violated. The City of Chicago, Cook County, and the United States federal government decided upon a 1.85-million-dollar settlement to nine plaintiffs. Later, more information regarding the assassinations of Hampton and Clark would show that Chicago Police had fired 99 shots and that it “was not coincidence” that the two killed in the raid were prominent Black Panther Party leaders. The posthumous documentary explores Hampton’s life as well as investigates his death. Evidence of the crime scene following the raid, re-enactments of the events, and interviews produced by Howard Alk and Mike Gray are all featured in their film.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-7JIR1u9qw