Experience the Hidden: Negro League Beisbol Exhibit at the Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum

Baseball is America’s pastime. The crack of a bat. The whiff of a pitch. The strategy, skill and luck fused into every inning. The atmosphere of the ballpark on a summer day or the suspense on an October night. Baseball is embedded into American DNA. But baseball has exhibited a similar dark history as the Country has. Up until 1947, African-Americans were unofficially banned from playing in the major leagues. Andrew “Rube” Foster did not let that stop him. In 1920, by gathering players from across the country, Rube Foster formed the Negro National League (NNL).

On display until October 30, the Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum (AAHM) will host the “Negro League Beisbol” exhibit on loan from the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. The exhibit includes information and artifacts from Negro League players both relating to central Illinois and abroad.

Josh “Brute” Johnson played catcher for NNL teams including the Homestead Grays, Cincinnati Tigers and New York Black Yankees. Johnson batted a .354 average in 84 at bats during his career. After baseball, from 1942-1945, he served his country in the U.S. Army where he acted out duties as a second-lieutenant for an anti-aircraft unit in the European Theatre of Operations. Upon returning from duty, Johnson would become an active member of the Illinois State Board of Education. Johnson later died in Springfield in 1999.

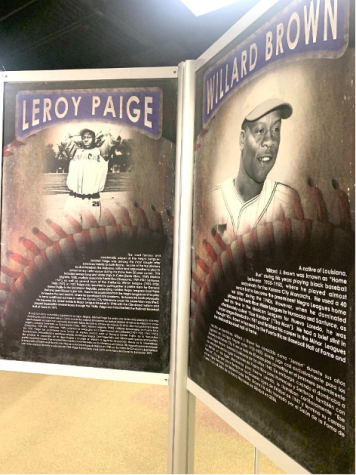

Leroy Robert “Satchel” Paige began his career in 1926 with the Negro Southern League where he quickly rose in the ranks. Paige then bounced from club to club in search of the best paycheck. In 1948, colorful Bill Veeck, maybe best known for the Chicago White Sox’s Disco Demolition Night in 1979, signed Paige to a contract with the Cleveland Indians. Paige would go 6-1 with a 2.48 ERA in 1948. Cleveland was already in the pennant race when Stachel was signed, Paige would be the first African-American to pitch in the World Series. Dr. Donald Spivey described Paige as, “arguably the greatest pitcher in the history of baseball”. Satchel Paige was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971. Paige occupied his time in Springfield as the Vice President of the Triple-A team Springfield Redbirds during their short stint as a St. Louis Cardinal affiliate.

Stories like Josh Johnson’s and Leroy Paige’s can be found at the AAHM. “Negro League Beisbol” was meant to make its way to Springfield in 2020 to celebrate the 100 year anniversary of Rube Foster’s formation of the Negro National League. Unfortunately, due to COVID-19 restrictions, the exhibition was unable to take place.

African-Americans were not the only ones involved in the Negro Leagues. Although baseball was founded in the United States, there are theories that the game was spread into Latin America with the building of the Panama Canal. The Cuban professional league integrated African-American players early in the 20th century just as the Negro National League did vice versa later on.

Thanks to Rube Foster and countless others, Major League Baseball did not always remain segregated. In 1911, Cuban-born stars Armando Marsans and Rafael Almedia were picked up by the Cincinnati Reds and made their first appearances, again paving the way. In 1947, Wesley Branch Rickey saw something others before had not. That same year, Jackie Robinson would break the color-barrier, making way for thousands after him.

The baseball-embedded DNA of Rube Foster, Jackie Robinson, Josh Johnson, Leroy Paige, Branch Rickey, Armando Marsans, Rafael Almedia and thousands of others was not discouraged by the blockades of racism within the United States. The idea that “it is just a game” is nanoscopic in regards to what has been accomplished as a result. Success not just changed the inner-workings of baseball but the social workings of society.

For more information about the exhibit visit: Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum – Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum (spiaahm.org)

All other statistics not cited are provided from the Springfield and Central Illinois African-American History Museum.