Ella Baker: A Mentor of Grassroots Politics

Ella Baker by CRMVETs

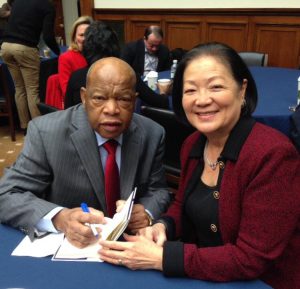

Black History Month is a complicated and sometimes contradictory concept. Ever since it was first conceived by Carter Woodson, the fight to put Black history in its proper, central place in the overall narrative has been an ever-changing effort. Figures like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Stokely Carmichael, Fredrick Douglass, and the late John Lewis are all honored throughout this winter month, and rightly so. But one name rarely gets mentioned despite her critical importance to the civil rights movement and American politics today. Known as a mentor and teacher among her fellow activists, the legendary activist Ella Baker is perhaps one of the most prolific and experienced activists in civil rights history. She is almost certainly one of the most prolific activists of the 20th century. Her emphasis on radical democracy, localized leadership, and interpersonal cooperation made her a model for intersectional political activism. Though excellent biographers like Barbara Ransby have given her some attention biographers like Barbara Ransby, her legacy has largely been ignored. That is a mistake. Baker’s legacy is an integral part of the American tradition of grassroots politics, and her story is critical to understanding the civil rights movement and political activism today.

A graduate of Shaw University and a valedictorian, Baker, represented a bold but well-rounded intelligence that many lacked. After she moved to New York City, she witnessed the suffering of the impoverished masses who were left without support during the Great Depression. Inspired by what she saw, Baker delved into the radical activist scene. She helped establish the Young Negroes Cooperative League, which sought to uplift African American communities and businesses. “Wherever there was a discussion, I’d go,” Baker would later say. “It did not matter if it was all men, and maybe I was the only woman… New York was the hotbed of radical thinking….”

By 1940, Baker joined the N.A.A.C.P. as a field secretary. There, Baker worked with experienced advocates like the suffragist Daisy Lampkin, who taught her the finer fundraising points and on the ground activism. As a field secretary, Baker was constantly on the move, serving as the NAACP’s direct link between its leadership and staff. Baker became so effective that Herbert Marshall, the NAACP’s D.C. branch president, predicted that she would have “a brilliant future.” She would end up operating on her own as a field secretary in 1941, working in Birmingham, Alabama. The city was notorious for its racism and described by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.” Activists were snatched readily and beaten half to death throughout the city. It was so bad that some had taken to calling the city “bombingham” for the local racists’ tendency to use firebombs. Baker, bold as ever, described the city as “one of the places in the South where I felt at ease.” Baker continued to work for the legal organization until she left it in 1956, with many criticisms levied at NAACP leadership.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Baker believed in what Dr. Ransby refers to as “radical democratic humanism” and sought to promote self-sufficiency for the people. To Baker, the way to destroy oppression was not with top-down leadership or lawsuits but to give the everyday person the means to find their own liberation and listen to their concerns and goals. Instead of leading the common people, Baker believed that those same people led movements. Describing her philosophy, Baker explained: “The major job was getting people to understand that they had something within their power that they could use, and it could only be used if they understood what was happening and how group action could counter violence….” To Baker, a movement was motivated not by its leaders but by the people on the ground.

Baker’s career did not end with the NAACP; She would soon take a position as the executive secretary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference after he asked her to help establish the organization. Through her connection with SCLC, she would establish a youth movement that would organize one of the most famous student movements in the civil rights era: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, aka SNCC.

Forming amid the sit-in movement, SNCC formed at Baker’s alma mater at a conference in April 1960. Thanks to Baker, Dr. King decided to fund the conference that allowed the organization to form. Baker’s emphasis on group-centered organization contributed to SNCC’s spirit, allowing it to organize around her philosophy. Baker explained this philosophy simply, saying, “If I had any influence, it lodges in the direction of the leadership concept that I believe in. Instead of having a leader-centered group, you have group-centered leadership.” At conventions, it was the official position of SNCC that all members were equal in the eyes of the organization and that every member could speak their mind and contribute to the movement’s planning. This strategy allowed figures like Stokely Carmichael and John Lewis to work under the same banner despite being politically distinct from one another. This deliberative and cooperative spirit would make S.N.C.C. unique and allow it to support operations such as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the March on Selma, Freedom Summer, and much more.

Even after the civil rights act was passed, SNCC would continue its work, pushing the boundaries of political and social change. Although it would disband in 1976, its organizing spirit – a spirit instilled by Baker – would remain in the activists it created. From that spirit, pan-African movements spawned, and a new generation of political organizers began in the Black Power movement. Though Baker passed away in 1986, her legacy and work continued. Whether through women like Diane Nash, or men like Congressman Lewis, Baker’s presence remained a powerful and transformative component of American political life long after her passing. There is much more to be done, but we are all beneficiaries of her democratizing work.