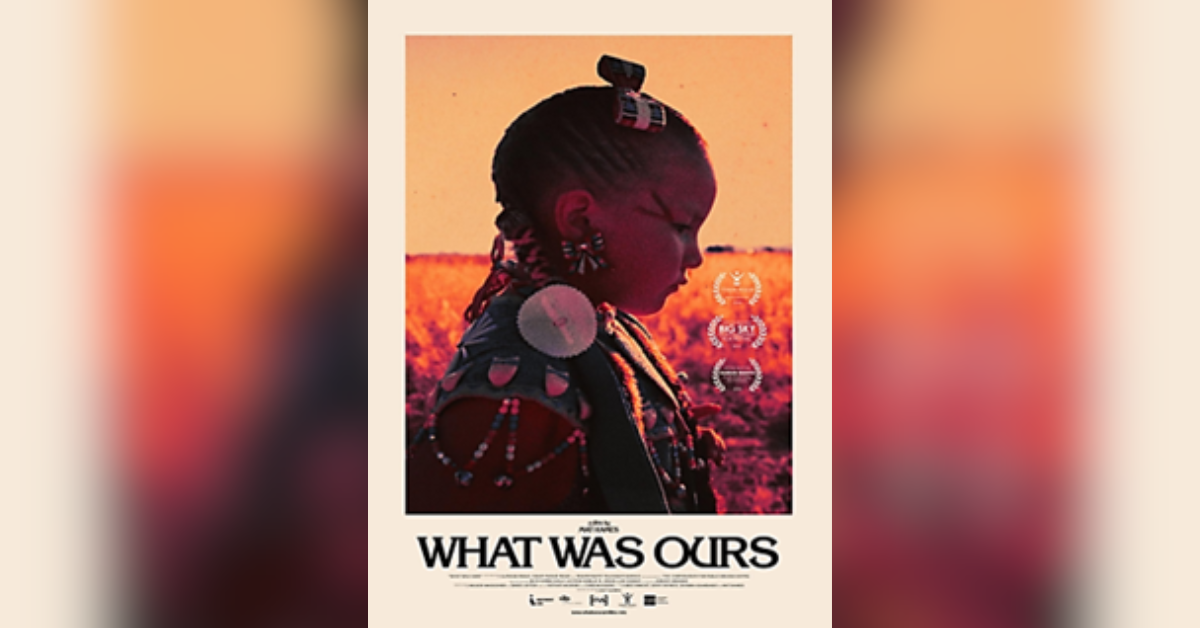

Last November, my son and I attended a viewing at the Illinois State Museum of a documentary, What Was Ours, which showed how modern-day Indigenous communities across the United States are trying to establish museums to honor ancestors and celebrate their cultures. Independent filmmaker Mat Hames, an Emmy award-winner, directed the film, which received the Best Documentary Feature at the American Indian Film Festival in 2018.

The documentary focuses on Jordan Dresser, a college graduate, Mikala SunRhodes, and Philbert McLeod, an elder from the Shoshone tribe. Jordan and Mikala are members of the Arapaho. Each wished to facilitate the return of historical cultural artifacts back to Wind River Reservation. The Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois invited Mikala, Jordan and Philbert alongside other community members from Wind River Reservation, to visit and view their collection. Mikala, Philbert and Jordan expressed hope throughout the film that what had been lost, could be returned. Ultimately, they left the Field Museum empty-handed. What Was Ours explored not only the complexity of how artifacts are lost from indigenous communities, but how such important cultural objects should be treated. The documentary also centered around why returning items to Indigenous communities is important. While institutions in possession of these objects allude to having good intentions, the purpose of the documentary reflects upon how returning sacred artifacts to their tribal communities can build not only trust, but a strong sense of community and unity despite the numerous losses they’ve faced in the past.

The Illinois State Museum in Springfield, Illinois has now covered exhibits pertaining to Native American items in their possession following legislative changes to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). These changes follow previous rules aimed to ensure that Indigenous descendant communities permit display of items which hold significant meaning. The objects under consideration are sacred, funerary, or cultural patrimony. Additionally, the new rules indicate that agencies in possession of ‘culturally unidentifiable human remains’ have a set time limit (5 years) to update information in relation to those remains and funerary objects.

The Illinois State Museum in Springfield, Illinois has now covered exhibits pertaining to Native American items in their possession following legislative changes to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). These changes follow previous rules aimed to ensure that Indigenous descendant communities permit display of items which hold significant meaning. The objects under consideration are sacred, funerary, or cultural patrimony. Additionally, the new rules indicate that agencies in possession of ‘culturally unidentifiable human remains’ have a set time limit (5 years) to update information in relation to those remains and funerary objects.

This gives considerable hope that in the future, Native American communities such as Wind River Reservation, will be able to rightfully receive culturally important artifacts and remains to their communities. This ensures that tribal communities can respect their ancestors, bringing honor to those who came before, while honoring their living descendants.