BEYOND | Spanish Flu vs. COVID-19: A Compare and Contrast

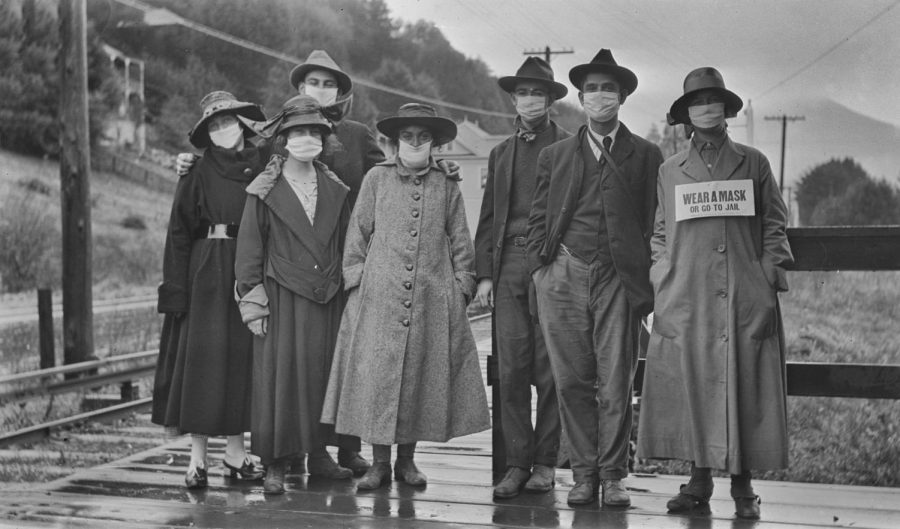

A group of people standing outdoors are shown wearing masks during the pandemic. One woman wears a sign, reading ‘Wear a mask or go to jail.” Niday Picture Library/Alamy

In 1917, the United States entered one of the deadliest wars in world history. Woodrow Wilson’s “Peace without Victory” speech was an interesting take on World War I, but with a new threat brewing domestically, victory or defeat were the only two options.

In 1918, the Spanish Flu, likely caused by bacteria from birds, ravaged parts of North America, Europe and Asia. Roughly 500 million persons became infected, equal to about one-third of the world population. Of those infected, it is believed that approximately 50 million died worldwide but some estimates believe that number could be closer to 100 million. For reference, around 750,000 people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19 through the duration of the current pandemic. The Spanish Flu pandemic attributed to roughly 675,000 American deaths despite the US population being less than one-third that it is today.

That is not to say COVID-19 should be taken lightly. According to Johns Hopkins Coronavirus research center, the mortality rate of COVID-19 in the U.S. sits at roughly 228 deaths per 100,000. To contrast, average flu and pneumonia cases result in around 15 deaths per 100,000.

If COVID-19 is not causing the same mortality rate as the Spanish Flu, why should we care? It is difficult to say whether or not the Spanish Flu was more highly transmissible than COVID-19. Medical research was still largely in its infancy during the early 1900s. Many hospitals were still largely operating through antiquated techniques. Medical technology was more or less ancient. U.S. health care spending made up just 0.25% of the nation’s GDP at the beginning of the 20th century. During the COVID-19 pandemic, health care spending hit an all-time high, encompassing 9.5% of the GDP.

The Flexner Report published in 1910, released through the Carnegie Foundation, called on US medical schools to enact stricter requirements for admission and graduation. Abraham Flexner, the author of the report, had found most medical schools at the time operated something like trade schools now operate. Most could graduate after just two years of education and homeopathy and electrotherapy were still largely taught. Flexner believed that by attenuating the talent pool and focusing solely on scientific evidence the medical field would flourish. The Flexner report is still regarded as a principle in medical education.

Mask and vaccine mandates have become a controversial and symbolic issue throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. This was not necessarily the case in 1918. The first mask mandates in 1918 primarily took place on the West coast where they were ultimately met with overwhelming support. Ordinances were so strict that, in fact, a mayor was arrested for not wearing one. Mayor John L. Davie of Oakland, California, heavily in favor of the ordinance, was smoking a cigar when officers walked past and demanded he wear it. After putting his mask on, the officers continued walking. Davie uncovered his face to continue smoking when the officer turned back around. Davie was arrested and posted his $5 bail.

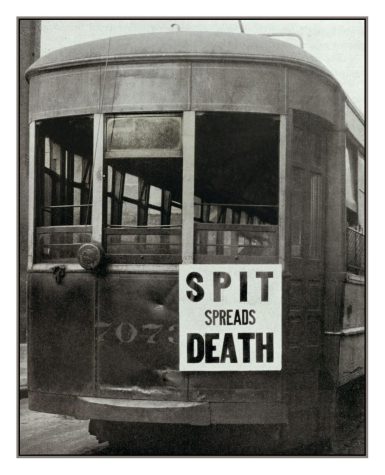

No U.S. state released mask mandates during the 1918 pandemic. However, the population was strongly encouraged. In Philadelphia, streetcars featured “Spit Spreads Death” signs. In New York City, no-spitting ordinances were put in place. People were encouraged to only sneeze or cough into a handkerchief, a now common practice.

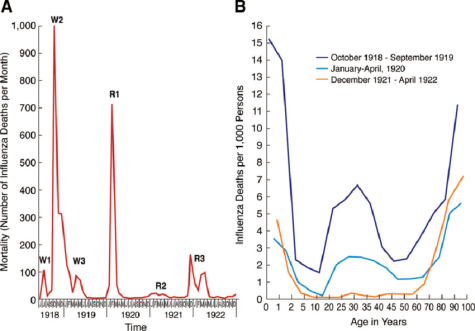

The pandemic operated in three distinct waves. The first, in the Spring of 1918, the second, most deadly, in the Fall of 1918 and the last, in the winter of 1919. The COVID-19 pandemic has seen similar fluctuations. The first major wave occurring fall/winter of 2020-’21, early Summer 2021, and late Summer/ early Fall of 2021. Some blame the Summer 2021 and current COVID-19 wave on the unvaccinated.

Unlike the 1950s polio vaccine, for which inventor Jonas Salk’s achievement was championed, the COVID-19 vaccine has been met with staunch pushback. COVID-19 vaccines have largely been made using mRNA. The use of mRNA therapeutics has primarily been used to treat tumors in cancer patients. mRNA in COVID-19 vaccines work as instructions, telling direct cells in the body to generate proteins to turn away or lessen the virus. COVID-19 mrRNA vaccines do not affect one’s DNA. That said, allergies and warning labels should be taken into consideration before dosage.

Why has there been such hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine? It is a puzzle to narrow the reason down to just one. Roughly 88% of one-year olds in the world have been vaccinated for tuberculosis, 86% for polio, and 85% for DTP3, measles and hepatitis B. A poll from the Kaiser Foundation found that conversations with friends and families played a major role in vaccination status. Did you learn or hear something that persuaded you to get vaccinated? Many of those who have received the vaccine in this category claimed they got vaccinated to protect friends and family, as well as seeing pressure from those same groups. That said, political theories, social media and tribe relations have certainly had a negative impact on vaccine numbers.

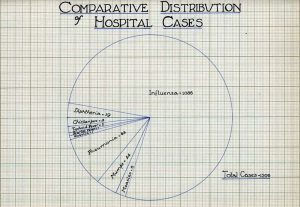

The 1918 pandemic saw no real vaccine development. Without specific diagnostic tools, it was difficult to determine whether or not the influenza virus was the culprit or a severe acute respiratory disease (SARS). On October 2, 1918, William H. Park, head bacteriologist of the New York City Health Department, was working on a Pfeiffer’s bacteria influenza vaccine. Park’s vaccine was given primarily to major companies and military camps. Roughly 39,000 doses of Park’s vaccine were given. By late 1918, New York Health Commissioner Royal S. Copeland described the vaccine attempt as an, “application of an old idea to a new disease.” In 1919, the American Journal of Public Health claimed that the causative organism was still unknown and vaccines had a trivial chance at targeting the right thing. A vaccine mixed by E.C. Rosenow from the Mayo Foundation had positive effects. The Rosenow vaccine was reproduced and administered to 500,000 patients.

As we have seen the COVID-19 virus mutate, the 1918 pandemic gives little hope for the future. While the Spanish Flu was under strong control following 1919, mutations have continued to harm human and animal life ever since. Almost all cases of influenza since the pandemic have been caused by descendants of the 1918 virus. These viruses have been spread throughout pigs, birds and humans. The 1918 virus contains genes specific to H2N2, H1H1, H3N2 lineage. Descendants of the 1918 pandemic virus still persist enzootically with pigs. However, all descendants of the 1918 pandemic caused substantially milder disease.

Is the COVID-19 virus native to China? Narrowing down a virus to a specific geographic location can be difficult. Before and after 1918, many influenza viruses can be traced back to Asia. However, the 1918 pandemic was first realized in North America. It could be argued that the virus got its start in Asia but historical and epidemiological data is too inadequate to date origin.

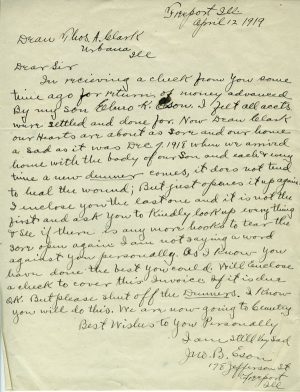

In more localized history, the University of Illinois stayed open during the 1918 pandemic. The reason behind the move was caused by low rates of retention in staff and students. In Champaign-Urbana, theatres and other public spaces closed their doors. The university put in a plan against the virus upping hospital beds from 30 to 400. Elmor Eson, one of 15 students infected, died from pneumonia symptoms. His father would write a letter to then Dean Clark asking to halt repeated requests for debt repayment.

A story in two periods, yet similarities are clear. Will COVID-19 be largely eradicated or will our grandchildren feel the mistakes of their elders?