Nameless but Reclaiming

In conjunction with the UIS Visual Arts Gallery reception of her works titled “Her Name Escapes Me,” intersectional multimedia artist Huong Ngo spoke about her experiences and their bigger-picture applications in last week’s ECCE: Speaker Series event “To Name It is to See it: Identity and Misrecognition.”

Both showings possessed similar themes of colonialism, intersectional feminism, immigration, identity, and political activism.

Ngo’s experiences as an immigrant from Hong Kong and refugee in the southern United States region, paired with the current political climate, provide the canvas on which she paints her story. Growing up, Ngo noticed patterns of inequality and a lack of fitting in with the majority of people in the United States based on constructed ideas of race. She attributed parts of this to the xenophobic rhetoric of fear utilized by the Bush administration, for instance, which is currently being perpetuated and normalized by the Trump administration.

University life exposed her to sexual assault, which allowed her to notice the places where oppression of women and minorities overlapped. Back in the early 1900s, it was seen as extremely suspicious for women to travel alone. Women seeking refuge synthesized marriages with men to slip under the radar, which led to copious instances of sexual and domestic violence. Ngo tells the stories of women who can no longer speak up or give their name to gatekeepers who decide to limit their power by keeping them anonymous.

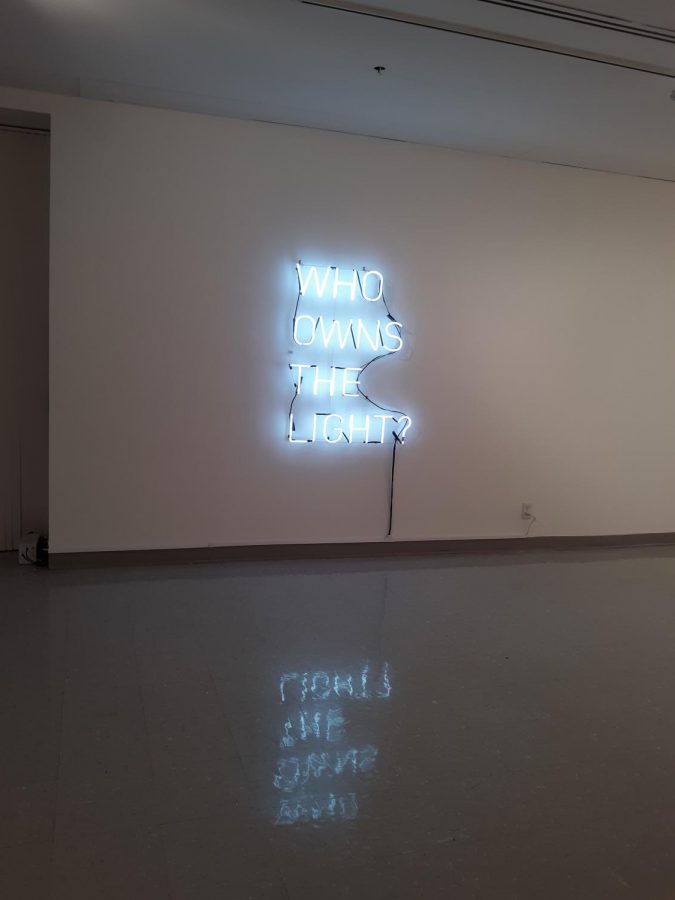

“Her Name Escapes Me” features multiple types of art with hidden statements about the self and institutions of power. Serigraph prints of Vietnamese women in colonial postcards bring many questions to the viewer, as the prints are almost too dark to reveal their contents. However, these giant postcards feature the women in an objectified manner, with the obscurity allowing them protection from being stared at. This seems to be the only feature of the exhibit in which being hidden holds agency. On the other side of the room lie books filled with pages of varying darkness, only revealing their print when touched. These pieces invite the viewer to consider how he or she fits in with the art and the way in which acknowledgment brings it to life. A pillow embroidered with the police report of an anonymous assault victim, a thoughtful neon sign, and infographic posters showing the many Vietnamese translations of the word “feminism” are also featured. This exhibit will be available for viewing in the Visual Arts Gallery in HSB 201 until November 21. For a list of available hours and dates, as well as contact information, visit www.uis.edu/visualarts/gallery.

In her ECCE presentation “To Name It is to See it: Identity and Misrecognition,” Ngo stressed the importance of telling the stories that are worth remembering. She invited the audience to ask themselves whether it is better to sacrifice the greater good of humanity for individual protection (perhaps illusory) or to rebel against isolationist regimes. Many of her exhibits displayed in museums such as DePaul Art Museum in Chicago, Ngo said, were like chapters of the story she is continually telling about her life and cultural history. Pictures and elaborations of all of her previous works can be viewed at www.huongngo.com/ in the “Works” tab.