BEYOND | The Pandemic Halted Research. As It Returns, It May be Forever Changed.

Identifying a species seems straightforward. It feels like one of those things you learn how to do when you are a toddler, but definitively telling the difference between one species and another is tricky when you get out in the field.

What if you are measuring how many different kinds of trees are in a forest? What if you have microscopic algae that all look the same even if they are different species?

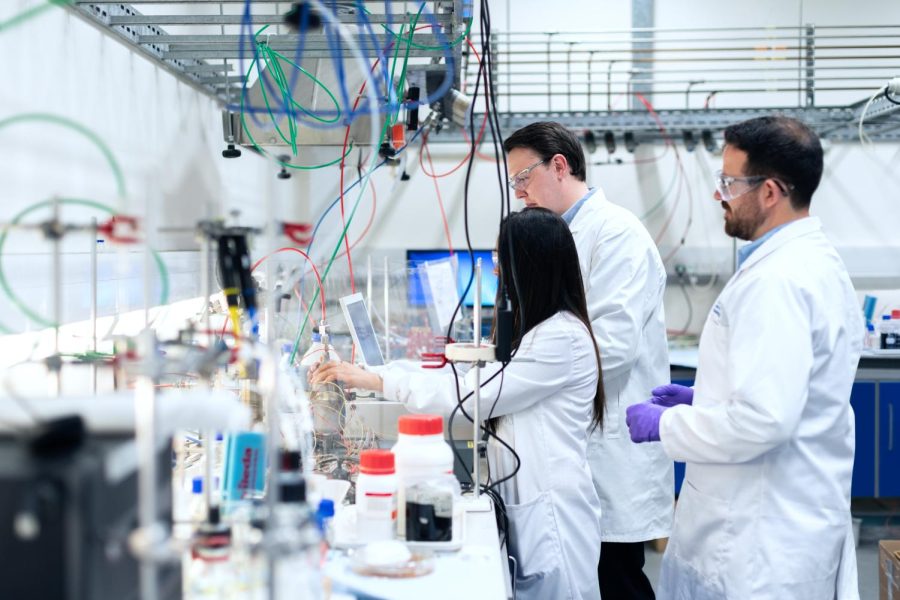

Lucia Vazquez, a professor of biology at UIS, has dedicated her career to understanding how the information stored in DNA can be used and she wants to make it easier to differentiate species.

Recently, she has been working on a method of telling species apart called DNA barcoding. Her team takes strings of DNA and looks for specific markers, little bands of DNA, that are unique to a species.

“Species identification is the basis for testing biodiversity,” said Vazquez.

She and a team of about a half dozen split their time between finding species-specific markers for oak trees and the kind of algae that can be toxic when it builds up in water supplies.

Then, in spring 2020, she got the same message many of us did: go home.

“We had to suspend all activities,” said Vazquez.

Though she and her team met over Zoom to discuss methods and go over other papers about barcoding, they could not get back into their lab until spring 2021, almost a year after leaving it.

And when she was able to get back to her lab and continue working, trouble continued.

“We couldn’t get material that’s essential to isolate DNA,” said Vazquez.

Basic lab chemicals like ethanol and pipette tips, which are essential for measuring precisely, were suddenly out of stock. It took months longer to get supplies.

This supply chain problem does not appear to be getting better anytime soon, which limits the kind of research that can be done.

“It’s uncertain at this point. My students and I are going to try to find an alternate method,” said Vazquez. “It’s going to not be the ideal situation.”

Not everyone has even had Vazquez’s experience of being able to get back into the lab.

“A good amount of my colleagues have just stopped doing research,” said Vazquez. “Some people are not feeling comfortable being in a face-to-face environment.”

A team of researchers from Northwestern University and Harvard had similar anecdotal observations as Vazquez, so they surveyed scientists in the United States and Europe to see how the pandemic had impacted academic research. The survey was conducted between April 2020 and January 2021 and was published in the journal Nature in October.

The team found that researchers are almost back to normal levels of time spent doing research, but there are still fewer new projects being started.

What’s more, this “disproportionately affects female scientists and those with young children,” according to the report’s authors.

These effects were seen across all fields of study, including the natural sciences, social sciences and humanities.

Richard Gilman-Opalsky, professor of political science at UIS, shared that he saw the pandemic’s complex impact on the social sciences.

“The research that is dependent on travelling to libraries, to do field research, to attend conferences to rehearse drafts of your scholarship, that couldn’t be conducted over a screen simply couldn’t happen,” said Gilman-Opalsky.

Still, he pointed out that for some, it provided a unique opportunity.

“Scholars were able to hunker down in office spaces. That mode of life enabled a lot of people in the social sciences and humanities to do their work,” said Gilman-Opalsky, before quickly pointing out that interrupted school and child care schedules made that mode of life impossible for some.

There is also, according to Gilman-Opalsky, another element that distinguishes his field from the natural sciences.

“Social science and humanities researchers were also forced to address the pandemic,” said Gilman-Opalsky. “It was not just a biological event. It was a social event.”

The complex social, political and psychological effects of the pandemic impacted nearly every aspect of the social sciences.

Beyond the challenges, research has also brought some elements to the academy that may be here to stay.

A survey of master’s and Ph.D. programs conducted by researchers at the University of Chicago identified several innovations which. The survey was conducted among deans at 208 institutions.

The team found that almost every institution surveyed, 94%, said they will permanently offer online and hybrid courses. Forty percent also expanded use of so-called “holistic” admissions practices.

Vazquez considers research often. She oversees “research and innovation” at the university and says there have been big changes to academic conferences.

“The majority of conferences were moved online,” she said.

This change could be good for institutional budgets and researcher’s personal wallets. Travel and lodging can be expensive.

“This is gonna be a game changer,” Vazquez said. “I think we’re gonna see it have a hybrid model.”

The future of research is uncertain, but it has been forever changed.