‘Cracking’ Illinois Redistricting

You know your state’s in trouble when everything—including the map itself—is corrupt.

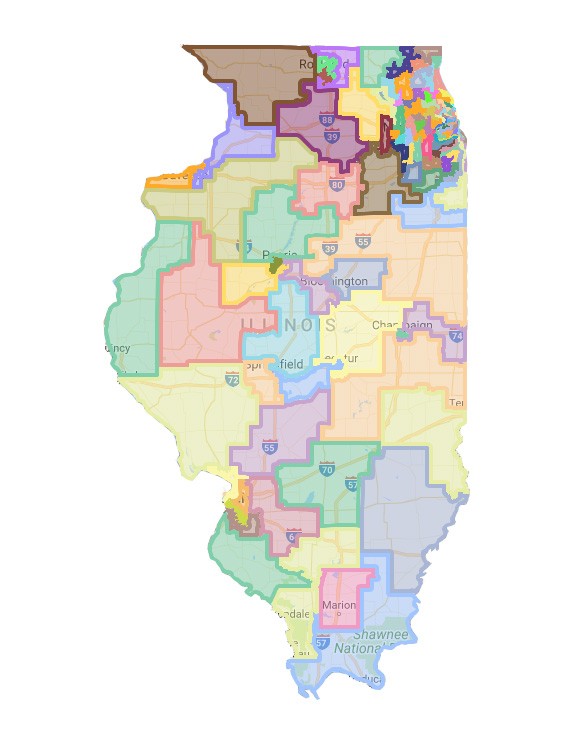

On the surface, Illinois’ district map looks balanced: each district has equal population, are compact, and are technically contiguous as the state constitution mandates. Like every other state in the country, Illinois is broken up into several smaller geographic districts. Voters from each district elect different officials, including state legislators and members of Congress.

Every decade, after the national Census, the Illinois state legislature will redraw district lines to account for population changes and to ensure that each district has about the same number of people. The idea is, if each district accurately reflects its constituents, then each voter will have an equal say.

Yet Illinois Democrats can manipulate the map in a way that only further solidifies their power, a practice commonly known as gerrymandering. There are two common techniques in gerrymandering: packing and cracking.

Packing concentrates all a party’s voters into one district,while cracking occurs when one party’s votes are spread out among several districts. While this problem doesn’t compare to states like Wisconsin or Texas, Illinois is special in that it is difficult to change the redistricting process here more than anywhere else.

Our current map

For a large part of Illinois’ political history, Republican candidates would run with the electoral strategy that assumed downstate districts and Chicago’s collar counties would be solidly Republican. But, as more Chicago residents started moving to the suburbs, the collars have been less and less solidly red.

The current district map, drawn in 2011, exacerbates this problem, making Chicago stretched split into eight different districts with most extending into the suburbs. By including only small amounts of suburban Republicans into “cracked” districts made up of mostly democratic Chicagoans, the Democrats were able to secure and even expand their power over the legislative and executive branches of government.

As a result, the new map shaped the state’s congressional districts in such a way that six congressional Republicans ended up in districts with other incumbents and thus were left vulnerable in the next election cycle. Many Republicans were now forced to run in districts where they didn’t live, making their chances at reelection that much more difficult.

Redistricting seemed to have its intended effect in that it elected more Democrats to office. Of the six congressional districts deemed to be competitive districts by the 2011 map, three were Republican pre-2011 and are currently Democratic, three were able to keep incumbent Democrats in power, and one was Democratic pre-2011 and has since turned Republican.

But, the Democratic reign over the redistricting process may not last for long. Although the General Assembly is responsible for drawing the map, the governor can veto. Gov. Bruce Rauner has already tried to take the redistricting process away from the legislature by backing a citizen-led initiative that a non-partisan third-party oversee creating district boundaries. The initiative would have changed the state’s constitution to try and take the politics out of boundary-drawing. In 2016, however, the Illinois Supreme Court prevented it from appearing on the fall ballot for citizens to vote on.

The future of gerrymandering

While the state Supreme Court’s decision was a clear win for Democrats, some say the party still might face another hurdle before the next census: The U.S. Supreme Court.

Justices are currently hearing a case that could put severe restrictions on the practice of gerrymandering, after Wisconsin’s state map was drawn so that the GOP received a 60-39 seat majority, despite garnering only 48.6 percent of the vote. While nearly all seven justices find partisan redistricting distasteful, the question is if it is unconstitutional. To what extent does gerrymandering provide citizens equal protection under the law? Does it infringe on citizens’ rights to freedom of speech?

A Wisconsin federal court ruled that the GOP-controlled legislature discriminated against Democrats using this standard as well as a mathematical formula designed to measure the “efficiency gap,” or how many “wasted” votes are in a district, according to The New York Times.

A wasted vote is defined as a vote that doesn’t contribute to winning additional districts. The efficiency gap identifies all wasted votes in a race for both parties. Thinking about Illinois, wasted votes would be considered all Republican votes that are purposefully split among majority-Democrat districts so that those votes don’t make a large difference in the election’s outcome.

By adding the total votes up, finding the difference between the two and then dividing that number by total number of votes in a state, political scientists can find a percentage number that shows the extent of partisan gerrymandering. According to the creators of the measurement, a gap of seven percent or more means that a state participated in unconstitutional redistricting.

Understanding these new considerations for measuring gerrymandering is at the heart of predicting Illinois’ political future. Because, in the end, even if the Supreme Court cracks down on gerrymandering, Illinois will likely be one of two states that will be able to continue to unfairly divide districts unscathed, the other being democratic New York. No test for measuring gerrymandering considers political geography, which is what Illinois Democrats exploit to maintain its power. Because most of Illinois’ democratic votes are naturally concentrated into the large urban center of Chicago, legislatures can easily “crack” votes based on the natural distribution of partisan affiliation.

As a result, Illinois’ district map looks balanced when it’s not.

Unless the Supreme Court were to decide that a third-party body must be responsible for drawing maps for every state (which could be a possibility but is considered a long-shot), Illinois is relatively safe from federal interference. And, as proven with the failed Rauner-backed citizen initiative, the only way Illinois can change the way it draws its districts is through a constitutional amendment from the legislature.

Given the fact that Democrats have a near three-fifths majority in both the House and Senate, that’s unlikely to happen any time soon.