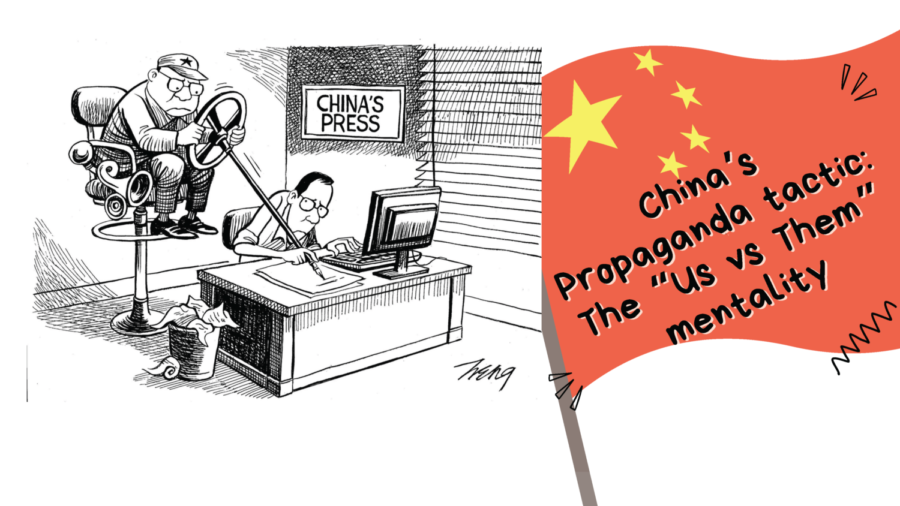

Living in China, I watched the daily national 7 p.m. news broadcast, which can be summarized into the central narrative that China is good and the West or any other country that the Chinese government does not get along with is terrible. Another critical part of Chinese propaganda is the emphasis on the actions of Communist Party leaders and a focus on positive news and achievements, all aimed at raising the government’s prestige and legitimacy in the eyes of the Chinese people [1].

The Chinese government’s most useful tool to tell its narrative is its Propaganda Ministry. This “omnipotent and omnipresent” body provides spiritual guidance for China’s media and, by extension, the broader population. The Propaganda Ministry’s tactics have a simple goal: to create the impression of consensus and uniformity… [1, chapter 2]. It achieves this by ensuring that all media outlets carry the same message – a tactic that creates a sense of uniformity, as ordinary people reading the papers, watching TV and surfing the Internet get the same message packaged in different ways. It has further created the Internet army — (paid Internet commentators called the Fifty-Cent Army, wu mao dang) – Individuals who post contents that endorse the government’s position on controversial issues [2]. Through all these ways, the Chinese government has reduced the activities of citizen journalists or online opinionated people.

The primary tool used by the Communist Party of China’s Propaganda Ministry is the “Great Firewall.” While this is primarily a censorship tool used by the Chinese government, it is also a propaganda tool because when words and topics such as the Taiwanese independence, the June 4, 1989 crackdown at Tiananmen Square, China’s suppression of the Falun Gong spiritual group, the Uighur genocide, accurate statistics of COVID-19 victims and other humanitarian disasters, that will end up showing the perfect utopian country that is full of peace and prosperity.

The simple and effective way this “Great Firewall” works is that the Propaganda Ministry influences internet and web firms to self-police their sites to ensure that banned words and phrases and banned topics never appear on their platforms [1, chapter 2]. In other words, to further control information, the Propaganda Ministry’s primary strategy is to hold Internet service providers and (information) access providers responsible for the behavior of their customers, so business operators have little choice but to censor content on their sites proactively. One way to do this is by paying human monitors to censor content manually [2].

Since its inception, the achievements of the Communist Party of China cannot be separated from the support of the party’s Propaganda Ministry’s news and public opinion work. Since the founding of the Communist Party of China in 1921, the Party’s news and public opinion were used to organize people to join the struggle against imperialism and feudalism. The Party news work played a vital role in mobilizing peasants during the agricultural revolution (土地革命 Tudi Geming). During the war of liberation (解放战争 Jiefang Zhanzheng), the Party’s news department focused on propaganda against the Kuomintang’s conspiracy to launch a civil war. After founding the People’s Republic of China, the Party’s news shouldered the mission of consolidating and propagating the construction of a socialist country led by Mao Zedong.

From the reform and opening period to present-day China, the Communist Party of China’s Propaganda Ministry still serves its purpose. During a visit to the three main Communist Party and state news organizations in 2016, China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, said, “All news media run by the party (who are all subordinates of the Propaganda Ministry) must work to speak for the party’s will and its propositions, and protect the party’s authority and unity [3].” China’s media outlets are essential to its political stability, and the leadership cannot afford to wait for them to catch up with the times.

References

- Young, D. (2012). The party line: how the media dictates public opinion in modern China. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shirk, S.L. (2011). Changing Media, Changing China. (2011). United Kingdom: OUP USA.

- The New York Times. (2016, February 22). Xi Jinping’s news alert: Chinese media must serve the Party. The New York Times.

Kehinde Bolu Adesina, a graduate of the University of Illinois, Springfield, holds a Master of Arts Degree (MA) in Communication. From August 2021 to May 2023, he served as the Multimedia Editor for The Observer. Over the years, his research has been dedicated to upholding the tenets of quality journalism, fostering informed public discourse, fortifying democratic foundations, and nurturing a more knowledgeable and resilient society, with a keen focus on countering disinformation, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and post-truth narratives in the digital landscape.