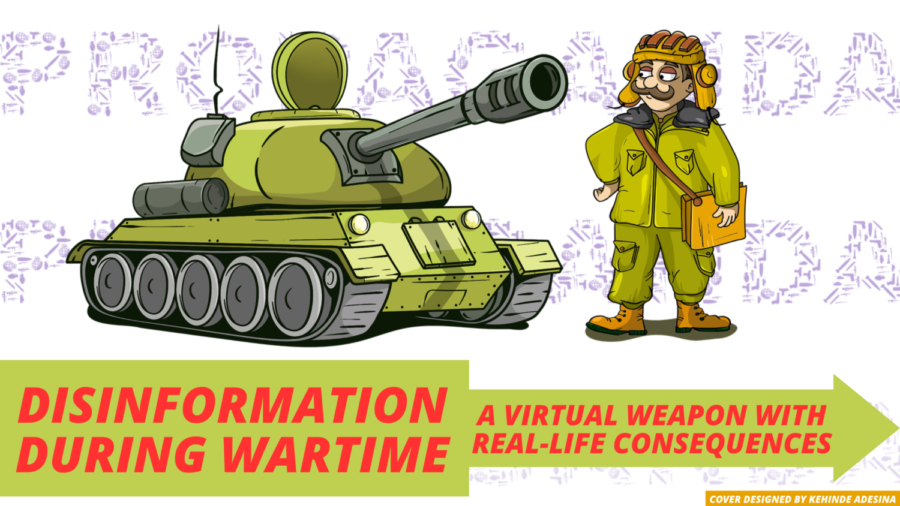

The term “fake news” is not new. Contemporary discourse, particularly media coverage, seems to define fake news as referring to viral posts based on fictitious accounts made to look like news reports [1]. Just as McNair (2017) said in Faking it in journalism: not really new, not exactly news, fake news did not just start today. An example of widespread misinformation dates back to 1938, when the broadcast of a radio adaptation of H. G. Well’s drama, The War of the Worlds, scared an estimated one million residents [2]

Over the years, news has always been criticized for being biased, plagiarized, falsified, fabricated, fictionalized, and, yes, faked. Brian McNair

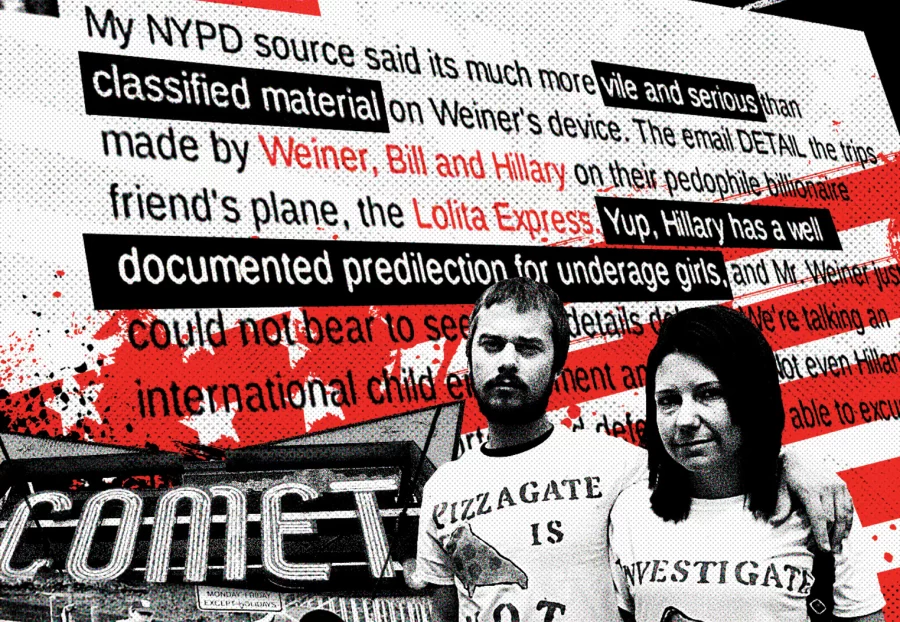

Making up of stories (in 1980, young American journalist, Janet Cook, made up a story about an eight-year-old heroin addict in Washington D.C., Jimmy. She invented, fabricated, and knowingly deceived her audience); publication of hoax (in 2004, The Guardian newspaper published on its front page a dramatic story of police in rural China beating a dissident — a hoax which never happened); conspiracy theories (beliefs that the moon landings were staged, the Illuminati are an actual thing and the Bible is literally true about the age of the Earth), human errors, postmodernism (any profession of truth is nothing more than a reflection of the political ideology of the person who is making it) [3] (McIntyre, 2018), and state propaganda (Russia, North Korea, China, etc.) have all contributed to the fake news in journalism.

Furthermore, the development of the Internet has taken information from the mainstream media and handed it over to ordinary citizens. However, advanced technologies mask reality, create illusions, and make it more difficult to access real news in this technologically advanced Internet age. In this era where “everyone has a microphone,” fake news emerges in an endless stream. A vivid example is some blogs and websites whose names can be mistaken for legitimate news sites. Their fake news is widely circulated on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

On the one hand, outrageous and fake stories that go viral—precisely because they are absurd—provide content producers with clicks that are convertible to advertising revenue. On the other hand, other fake news providers produce fake news to promote particular ideas or people they favor, often by discrediting others [4]. I believe that the curiosity of internet users and the lack of professional ethics of some journalists are the subjective reasons for the propagation of fake news. Another reason why fake news is so rampant on social media is the lack of media literacy on the part of the audience.

Question

So here is the question: What do real journalists have to do to win back the audience’s trust in this age of fake news on social media, and how can the audience consume less fake news on social media?

Truth is the life of journalism and the professional and moral bottom line that journalists should adhere to. Fake news, fabricated out of thin air, erodes the authenticity, obliterates the core essence of news, and violates the fundamental principles journalists should follow. In this digital media age, journalists should shoulder the arduous mission of resisting the dissemination of biased, plagiarized, falsified, fabricated, fictionalized, and faked news. Still, they should disclose the truth to society in a timely, factual, and accurate manner and bravely fight to end fake news.

The people who get information from the Internet should increase their media literacy, i.e., they must learn to evaluate the authenticity of online information. In their book “Blur: How to know what’s true in the age of information overload,” Kovach and Rosenstiel [5] put “truth” at the heart of news reporting. Like them, I believe that seeking the truth remains the purpose of journalism—and the object for those who consume it. In this book, they shared the 6 Ways of Skeptical Knowing—Six Essential Tools for Interpreting the News. They told information consumers to ask themselves the following questions.

- What kind of content am I encountering?

- Is the information complete? If not, what’s missing?

- Who or what are the sources, and why should I believe them?

- What evidence is presented, and how was it tested or vetted?

- What might be an alternative explanation or understanding?

- Am I learning what I need?

In conclusion, insisting on truth is not just a matter of personal perception. It is also a matter of professional, social, and political responsibility. Promoting reliable information in society requires a public ethical environment consistent with it. Knowledgeable citizens should prioritize maintaining information authenticity over electing a Republican or Democratic president (in the USA) or a PDP, APC, or LP president (in Nigeria) based on the propaganda that they “blindly” consume in the media, especially in the Internet age. When you see a news article or a piece of information online, ask yourself the questions above before reacting to or even believing them.

Works Cited

- Tandoc Jr, E. C., Lim, Z. W., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining “fake news” A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital journalism, 6(2), 137-153.

- McNair, B. (2017). Fake News: Falsehood, Fabrication, and Fantasy in Journalism (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315142036

- McIntyre, L. (2018). Post-truth. MIT Press.

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of economic perspectives, 31(2), 211-236.

- Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2011). Blur: How to know what’s true in the age of information overload. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Kehinde Bolu Adesina, a graduate of the University of Illinois, Springfield, holds a Master of Arts Degree (MA) in Communication. From August 2021 to May 2023, he served as the Multimedia Editor for The Observer. Over the years, his research has been dedicated to upholding the tenets of quality journalism, fostering informed public discourse, fortifying democratic foundations, and nurturing a more knowledgeable and resilient society, with a keen focus on countering disinformation, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and post-truth narratives in the digital landscape.